But you tell me over and over and over again, my friend

Ah, you don't believe we're on the eve of destruction.(Eve of Destruction by Barry McGuire, 1965)

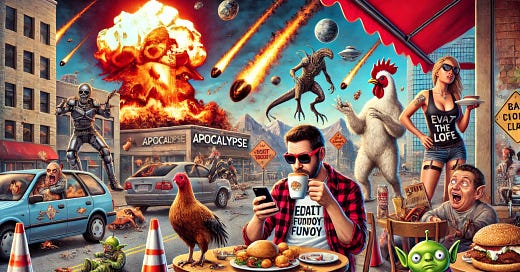

Throughout history, humans have consistently overestimated the importance of current events, using them to forecast impending doom. History cycles through fears of the world's end, but the end is rarely as near as we think.

The Late Great Planet Earth, by Hal Lindsey, was a 1970 book that predicted an approaching apocalypse as early as 1988 based on wars, Israel’s restoration, and a whole slew of miscellaneous moral decline. Lindsey anticipated a global leader—the Antichrist—who would deceive the world, unite nations under a false peace, and be overthrown by the return of Jesus Christ. Lindsey died last year, never having quite seen the future he envisioned. (Although Donald Trump meets some criteria of the Antichrist Lindsey described.)

I’m as guilty as anyone of reading too much into news and theories. In high school in the early 80s, I wrote a sci-fi story called "When the Sun Dies." Its premise was based on a since-resolved solar neutrino problem that suggested the sun was further along on the stellar main sequence than scientists initially thought. In my story, the sun would become a red giant and engulf the Earth in our lifetime instead of over millions of years.

It’s an example of assuming that A will necessarily lead directly to B, which is not always true, especially when the science is imperfect.

In 1982, as part of our college tutorial, the incoming freshman class was required to read Jonathan Schell’s The Fate of the Earth, an exploration of nuclear war’s catastrophic consequences. Schell outlined how the use of atomic weapons would lead to human extinction. Another forty-some years on, though nuclear war is always a possibility, conventional warfare remains the predominant method of dominion and defense.

In 1988, after graduating from college and a few years in the workforce, I contributed again to the apocalyptic milieu by writing a song called “There's Something Wrong with the Sky, " a global warming ballad about how life on earth would be wiped out due to climate issues. My song ends as John Lennon’s Imagine begins: “Imagine there’s no heaven. It’s easy if you try.”

Fast-forward another twelve years, and at midnight on January 1st, 2000, the millennium rolled over despite Y2K's apocalyptic fears and Prince’s statement in the song 1999, “2000-0-0 party over, Oops, out of time.”

Here we are in 2025, a quarter of a century later. The world (or most of it) is still here, and in some cases, people are thriving. Under Trump 47, we are facing many suggestions that the world, as we knew it, is over, that a new world order has begun, and that we have regressed eighty years to the period just after WWII.

Eighty years is an interesting length of time. It’s conveniently longer than the average human life, so it seems forever.

Apocalyptic thinking is comforting.

I remember thinking when I was younger (long before having children changed how I viewed the future) that it might be great if I were part of the last generation to walk the earth. Apocalypse in any form would be the ultimate cure for FOMO because I wouldn't miss anything.

Every generation experiences unprecedented change.

The fall of Rome probably felt like the end of civilization if you were Roman.

Some felt the 2020 global pandemic was the end of the world. Five years later, it doesn’t appear to have been so. The 1918 Spanish Flu killed almost 5% of the global population and was the most devastating in history, and the Black Death in the 14th Century killed more than a third of Europe. Even the Industrial Revolution, which changed so much and brought us into the machine age, didn't change us fundamentally as human beings. We still need nature, healing, and sleep. Writing a good poem or essay is perhaps more challenging than before, despite (or even because of) the advent of advanced typing machines and computers.

History tends to frame things in terms of cycles of doom and rebirth. The 1960s may have been the dawn of the Age of Aquarius. But recent history shows we didn't accomplish much after that period of flower power and free love. Black people still don't have equality in America, and women don’t get equal pay for equal work. The Cold War ended, the Berlin Wall fell, and we're left with a precarious world order with threats of wider war left and right as much if not more than ever

People forget how much stays the same even as many things change. Dylan's song “The Times They Are A-Changin.,” has been on my mind since the recent Timothy Chalamet film, “A Complete Unknown.” The song suggests that things will change no matter what you do, so you'd better get used to it. But it cautions trying to explain what’s going to be the outcome: “Don’t speak too soon / For the wheel’s still in spin.” Maybe it's about chaos and uncertainty and how history moves forward without asking permission.

Come writers and critics

Who prophesize with your pen

And keep your eyes wide

The chance won't come again

And don't speak too soon

For the wheel's still in spin

And there's no tellin' who

That it's namin'

For the loser now

Will be later to win

For the times they are a-changin'.

The Who's “Won’t Get Fooled Again” is an apt answer to how much stays the same after upheaval and revolution: “Meet the new boss. Same as the old boss,” Roger Daltry howls at the song’s end. In writing the song, Pete Townshend said he was partly inspired by India's spiritual leader, Meher Baba, who said we should reject blind faith in any political movement and emphasize personal integrity instead.

Is it the end of the world? If history has any lessons for us, probably not.

Is it a time to be vigilant? Always.